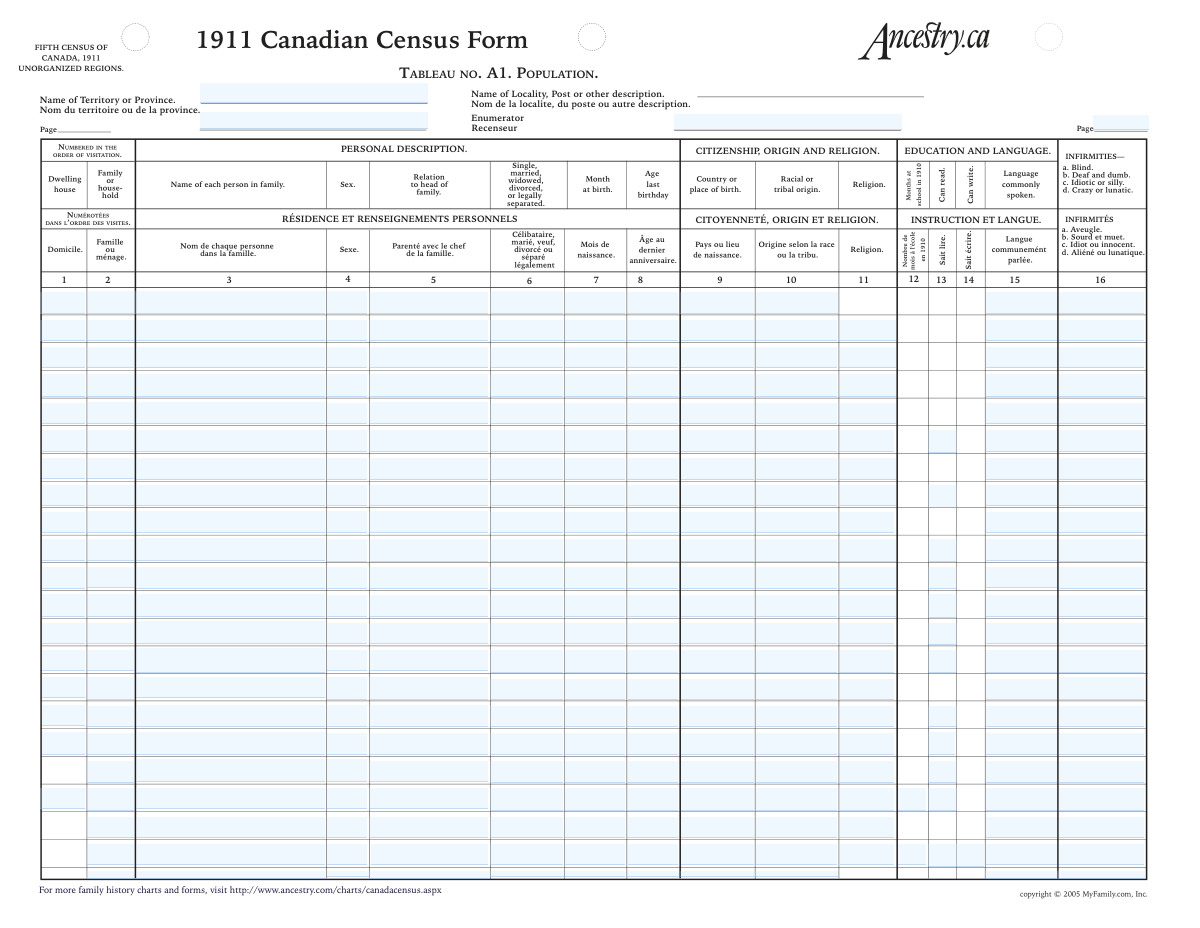

Yes! You can use AI to fill out Fifth Census of Canada, 1911 (Canadian Census Form) — Table A1: Population (Personal Description)

The 1911 Canadian Census Form is an official population schedule from the Fifth Census of Canada used by enumerators to document each household in a territory/province, listing every person and key demographic details (e.g., sex, relationship to head, marital status, racial/tribal origin, birthplace, month of birth, age, language, religion, schooling, literacy, and infirmities). It is important for historical, genealogical, and demographic research because it provides standardized, line-by-line records that can be indexed and compared across households and regions. The form also includes header fields (territory/province, locality, enumerator, page) that help identify where and by whom the census was taken. Today, this form can be filled out quickly and accurately using AI-powered services like Instafill.ai, which can also convert non-fillable PDF versions into interactive fillable forms.

Our AI automatically handles information lookup, data retrieval, formatting, and form filling.

It takes less than a minute to fill out Canada Census 1911 (Table A1) using our AI form filling.

Securely upload your data. Information is encrypted in transit and deleted immediately after the form is filled out.

Form specifications

| Form name: | Fifth Census of Canada, 1911 (Canadian Census Form) — Table A1: Population (Personal Description) |

| Number of pages: | 1 |

| Filled form examples: | Form Canada Census 1911 (Table A1) Examples |

| Language: | English |

Instafill Demo: How to fill out PDF forms in seconds with AI

How to Fill Out Canada Census 1911 (Table A1) Online for Free in 2026

Are you looking to fill out a CANADA CENSUS 1911 (TABLE A1) form online quickly and accurately? Instafill.ai offers the #1 AI-powered PDF filling software of 2026, allowing you to complete your CANADA CENSUS 1911 (TABLE A1) form in just 37 seconds or less.

Follow these steps to fill out your CANADA CENSUS 1911 (TABLE A1) form online using Instafill.ai:

- 1 Go to Instafill.ai and upload the 1911 Canadian Census Form PDF/image (or select the form template if available).

- 2 Choose the census page/rows you are entering (household and person lines) and confirm the document language/format (English/French headings).

- 3 Enter or import the header details (territory/province, locality/post description, enumerator name, and page numbers).

- 4 For each household, fill in dwelling and family/household numbers, then add each person’s name, sex, and relationship to the head of family in the correct row order.

- 5 Complete personal and origin details for each person (marital status, racial/tribal origin, country/place of birth, month of birth, and age at last birthday).

- 6 Fill education/language and religion fields (language commonly spoken, religion, months at school in 1910, and can read/can write indicators).

- 7 Review AI-extracted entries against the source, correct any transcription issues (especially names, places, and codes for infirmities), then export/download the completed fillable form for saving or sharing.

Our AI-powered system ensures each field is filled out correctly, reducing errors and saving you time.

Why Choose Instafill.ai for Your Fillable Canada Census 1911 (Table A1) Form?

Speed

Complete your Canada Census 1911 (Table A1) in as little as 37 seconds.

Up-to-Date

Always use the latest 2026 Canada Census 1911 (Table A1) form version.

Cost-effective

No need to hire expensive lawyers.

Accuracy

Our AI performs 10 compliance checks to ensure your form is error-free.

Security

Your personal information is protected with bank-level encryption.

Frequently Asked Questions About Form Canada Census 1911 (Table A1)

This form records a household’s population details from the 1911 Census of Canada, including names, relationships, birth details, origin, language, religion, education, and infirmities. It’s commonly used for genealogy, historical research, and transcribing census records into a structured format.

Modern users typically fill it out when transcribing an existing 1911 census page (for example, from an archive or genealogy site) into a clean, searchable record. You generally do not complete it from memory—use the original census image as your source.

Have the original 1911 census page image (or a clear copy) for the correct locality and household. You’ll also want the header details (territory/province, locality/post description, page number, enumerator) and each person’s line entries.

Enter names exactly as recorded on the census, including spelling variations, abbreviations, or ordering. If the census lists surname first or uses initials, keep that format unless your project instructions say otherwise.

It’s the number the enumerator assigned to group people living in the same household (often shown in the first columns for each row). Use the number shown on the census line for that person/household, not a number you create yourself.

Copy the relationship term used on the census (e.g., Head, Wife, Son, Daughter, Boarder, Servant/Lodger). If the census uses abbreviations, you can keep them as-is or expand them only if your transcription rules allow it.

Enter the marital status exactly as recorded on the census for that person. If the field is blank or unclear, leave it blank or add a note in your own records rather than guessing.

Transcribe the place exactly as written (e.g., “Ontario,” “Scotland,” or “England”), including province/state if shown. Don’t standardize to modern country names unless your project specifically requires standardization.

Use the same style shown on the census—either a month name/abbreviation or a numeric month. If the census is ambiguous, choose a consistent format for your transcription project and document your choice.

It’s the person’s age in years at their most recent birthday before the census date. Enter the number exactly as recorded, even if it seems inconsistent with the birth month or other details.

Copy the origin exactly as written (for example, “English,” “Irish,” “Scottish,” “Cree,” “Ojibway”). Because terminology is historical and may be outdated or offensive today, transcription is usually done verbatim for accuracy.

The form lists infirmities such as a) blind, b) deaf and dumb, c) idiotic/silly, d) crazy/lunatic (with French equivalents). Enter the letter code(s) or the exact wording shown on the census line, and leave it blank if none are recorded.

Check or mark these fields only if the census indicates the person can read or can write. If the census uses symbols, ticks, or abbreviations, reproduce the intended meaning as consistently as possible.

Yes—AI tools can speed up transcription by extracting text from the census image and mapping it into the correct fields. Services like Instafill.ai use AI to auto-fill form fields accurately and save time, while you still review for historical handwriting and spelling.

Upload the census PDF (or image) to Instafill.ai, select the form, and let the AI auto-fill the fields; then review and export the completed document. If your PDF is flat/non-fillable, Instafill.ai can convert it into an interactive fillable form before auto-filling.

Compliance Canada Census 1911 (Table A1)

Validation Checks by Instafill.ai

1

Required-per-person core fields present (Name, Sex, Age, Relationship, Household/Family identifiers)

For each populated census row, require a minimum set of fields to be present: the person’s full name, sex, age at last birthday, relationship to head, and the dwelling/household/family number(s) used to group the household. This prevents creating “orphan” person records that cannot be linked to a household or interpreted correctly. If any required core field is missing for a row that otherwise has data, the submission should be rejected for that row (or flagged for correction) and the user prompted to complete the missing fields.

2

Full name format and non-placeholder validation

Validate that each “Name of person” entry contains at least a surname and given name (or a clear multi-part name) and is not a placeholder such as “unknown,” “n/a,” or a single character. Names should allow punctuation commonly found in historical records (hyphens, apostrophes) but disallow purely numeric strings. If validation fails, the system should block saving the row or require confirmation with a reason (e.g., “name illegible on image”).

3

Sex field constrained to accepted values

Ensure sex is recorded using allowed values consistent with the form (e.g., M/F, Male/Female, or the exact census notation). This standardization is important for downstream indexing, searching, and consistency checks (e.g., spouse relationship logic). If an invalid value is entered, the system should reject the value and prompt the user to select/enter an accepted option.

4

Age at last birthday is an integer within plausible bounds

Validate that age at last birthday is a whole number (no decimals, no text) and falls within a plausible human range (e.g., 0–120, with configurable upper bound for historical data). This prevents transcription errors like “200,” “1/2,” or “ten” that break analytics and family reconstruction. If the age is outside bounds or not an integer, the system should flag the row and require correction or an explicit override note.

5

Month of birth normalization and validity (1–12 or recognized month names/abbreviations)

Accept month of birth as either a number (1–12, optionally zero-padded) or a recognized month name/abbreviation (e.g., Jan, January; French variants if supported). Reject values outside 1–12 and unrecognized strings to avoid ambiguous or unusable dates. On failure, the system should prompt the user to correct the month or choose from a controlled list, optionally storing both raw and normalized values.

6

Age-to-birth-month consistency check (soft plausibility)

Where both age and month of birth are provided, perform a plausibility check against the census year (1911) to detect obvious contradictions (e.g., age 0 with birth month far outside a plausible window depending on enumeration date assumptions). This helps catch swapped fields or misread digits (e.g., 19 vs 9). If inconsistent, the system should warn (not necessarily block) and request user confirmation or correction.

7

Marital status constrained to enumerated categories

Validate marital status against the form’s allowed set: Single, Married, Widowed, Divorced, Legally separated (including common abbreviations like S/M/W/D/LS if supported). Standardizing these values is critical for household relationship logic and demographic reporting. If an unrecognized status is entered, the system should reject it and require selection from the allowed list (with an “Other/Illegible” option only if explicitly supported).

8

Marital status vs. age plausibility

Apply a plausibility rule that flags very young ages with marital statuses that are unlikely (e.g., age under a configurable threshold such as 12–14 marked as Married/Widowed/Divorced). This does not assume impossibility but helps identify transcription mistakes. If triggered, the system should generate a warning requiring confirmation or correction before final submission.

9

Relationship-to-head controlled vocabulary and household coherence

Validate relationship to head against a controlled vocabulary (e.g., Head, Wife, Husband, Son, Daughter, Boarder/Lodger, Servant) while allowing historically common variants. Additionally, within the same family/household number, ensure at least one person is marked as Head and that multiple Heads are flagged for review. If invalid or incoherent, the system should block invalid relationship values and warn on household-level inconsistencies.

10

Spouse relationship consistency with sex (where applicable)

If a person’s relationship is Wife or Husband, validate that the sex value is consistent with the relationship label (unless the system explicitly supports non-binary/ambiguous historical transcription handling). This check catches common data-entry swaps between sex and relationship fields. If inconsistent, the system should warn and require the user to confirm or correct either the relationship or sex.

11

Dwelling/house number and family/household number are positive integers and properly formatted

Validate that dwelling house number and family/household number fields contain positive integers (no letters, no decimals) and are not empty when a row is populated. These identifiers are essential for grouping individuals into the correct household and preserving the census visitation order. If invalid, the system should reject the entry and prompt for a numeric value, optionally allowing a documented “illegible” marker if supported.

12

Household grouping consistency across rows

Within a submission, ensure that people sharing the same dwelling/household/family number have consistent grouping (e.g., the same dwelling number should not map to multiple unrelated family numbers without an explicit reason, depending on the data model). This prevents accidental mis-grouping when transcribing multiple households on one page. If inconsistencies are detected, the system should flag the affected rows and require review before acceptance.

13

Country/place of birth non-empty and not numeric-only; supports structured place patterns

Validate that country/place of birth is not blank for populated rows and is not a numeric-only value. Allow common historical formats such as “Ontario, Canada” or “Scotland” while rejecting obvious invalid entries (e.g., “1234”). If validation fails, the system should prompt for correction and optionally suggest standardized place names while preserving the original transcription.

14

Racial/tribal origin field presence and character validation

Where the form requires racial/tribal origin for a row, ensure the field is present and contains reasonable text (letters, spaces, hyphens) rather than symbols-only or numeric-only content. This improves searchability and reduces garbage values that undermine indexing. If invalid or missing when required, the system should block submission for that row or flag it as incomplete.

15

Infirmities/disabilities code validation (a–d or recognized terms) and de-duplication

Validate infirmities entries to match the form’s coding scheme (a=Blind, b=Deaf and dumb, c=Idiotic/silly, d=Crazy/lunatic) or accepted textual equivalents, and prevent duplicate codes in the same field. This ensures consistent interpretation and avoids ambiguous free-text that cannot be reliably analyzed. If invalid codes/terms are entered, the system should reject them and prompt the user to use the allowed codes/terms or leave blank if none.

16

Literacy fields mutual exclusivity and completeness (Can read / Can write / Cannot write)

Ensure literacy indicators are logically consistent: a person cannot be simultaneously marked as “Can write” and “Cannot write,” and checkbox fields should be boolean (checked/unchecked) rather than arbitrary text. Where both “Can write” and “Cannot write” exist, enforce mutual exclusivity and optionally infer missing values only if the business rules allow it. If conflicting selections occur, the system should block finalization for that row until the conflict is resolved.

Common Mistakes in Completing Canada Census 1911 (Table A1)

People often treat the “Dwelling house (order of visitation)” number and the “Family/household number” as the same identifier, especially because both are numeric and appear repeatedly across rows. This can mis-group individuals into the wrong household or make it look like multiple families lived in one dwelling (or vice versa), which breaks household structure and downstream indexing. To avoid it, copy each number exactly from its specific column and keep the dwelling number consistent for everyone in the same physical dwelling while the family number groups the family unit. AI-powered tools like Instafill.ai can help by mapping each value to the correct field and flagging inconsistent numbering across rows.

A very common error is typing the person’s residence (province/territory where they lived in 1911) into “Country or place of birth,” because both are location fields and the form header also references territory/locality. This changes the historical meaning of the record and can lead to incorrect family history conclusions and failed matches in genealogy databases. Always transcribe the birthplace exactly as written on the census line (including province/state if shown), even if it seems outdated or surprising. Instafill.ai can reduce this by validating that “place of birth” fields contain plausible birth locations and by keeping residence/header fields separate from person-level birth fields.

The form allows month names or numeric months, and users often mix formats across rows (e.g., “Jan”, “January”, “1”, “01”) or enter a full date when only a month is requested. Inconsistent formatting makes the dataset harder to search/sort and can cause import or validation issues in systems expecting a consistent month style. Use the same format the census uses for that entry (or a consistent standard your project requires), and do not add day/year unless the field explicitly asks for it. Instafill.ai can automatically normalize month formats (e.g., converting “1” to “01” or “Jan”) while preserving the original transcription when needed.

Users frequently calculate age from a birth year, round ages, or enter the age the person will turn later in the year rather than the “Age at last birthday” shown on the census. This creates internal inconsistencies (e.g., siblings’ ages out of order) and can cause mismatches with other records. The safest approach is to transcribe the age exactly as recorded on the census line, even if it appears off by one. Instafill.ai can help by flagging ages that conflict with the recorded month of birth or household relationships and prompting a re-check against the source.

Because the form lists specific categories (single, married, widowed, divorced, legally separated), people often enter modern shorthand (e.g., “partnered,” “common-law,” “N/A”) or infer status from relationships rather than copying what’s recorded. This can lead to invalid values and misinterpretation of the enumerator’s original classification. Avoid guessing—enter the marital status exactly as written (or use the closest allowed category if you are standardizing, but keep a note of the original). Instafill.ai can enforce allowed-value lists and prevent non-standard entries from being saved.

The “Racial or tribal origin” field is often mistakenly filled with a country (e.g., “Canada”) or a citizenship concept because the form also contains “Country or place of birth,” language, and religion nearby. This reduces data quality and can distort demographic analysis or genealogical interpretation. Enter the origin exactly as recorded (e.g., “English,” “Irish,” “Cree,” “Ojibway”), and do not substitute birthplace or passport nationality. Instafill.ai can help by detecting when a value looks like a country and prompting you to confirm whether it belongs in birthplace instead.

The infirmities section uses specific lettered categories (a blind, b deaf and dumb, c idiotic/silly, d crazy/lunatic), and users often type “none,” add modern medical terms, or place the letter in the wrong person’s row. This can create inaccurate or offensive records and breaks compatibility with systems expecting the original code scheme. Only record what is explicitly marked for that person, using the same code/wording shown, and leave it blank if nothing is recorded. Instafill.ai can validate that only allowed codes/terms are entered and can keep the codes aligned to the correct census row.

People sometimes enter the head’s name (e.g., “John”) or a vague description (“family”) instead of a relationship role (Head, Wife, Son, Daughter, Boarder, Servant, Lodger). This makes household structure unusable for analysis and can cause errors when building family trees. Use a clear role term as recorded on the census, and ensure it is relative to the head of household (not relative to the person above). Instafill.ai can help by offering standardized relationship options and flagging unlikely combinations (e.g., multiple “Head” entries within the same family number).

Because literacy appears as checkboxes and sometimes includes a “cannot write” indicator, users often check both “can write” and “cannot write,” or leave all literacy fields blank even when the census indicates a value. This creates contradictory records and reduces the reliability of education/language analysis. Follow the census marks exactly: check only the boxes that are marked, and use “cannot write” only when explicitly indicated. Instafill.ai can prevent contradictory selections by enforcing mutual exclusivity and prompting completion when a related literacy field is partially filled.

Users frequently “correct” spellings, expand initials, reorder given/surname, or modernize accents, especially on bilingual (French/English) forms. While well-intentioned, this can break source fidelity and make it harder to match the entry to the original census image or to other indexed records. Transcribe the name exactly as written on the census line, and if you need a standardized version, store it separately as an alternate name. Instafill.ai can help by preserving an exact transcription while also generating a standardized variant for search, reducing the temptation to overwrite the original.

Because the form repeats the same fields for many numbered rows (e.g., “Twelfth Census Row,” “Thirteenth,” “Seventeenth”), it’s easy to shift data up/down by one line when copying from an image or notes. This causes cascading errors where every subsequent person’s birthplace, month, age, and status are attached to the wrong name. To avoid it, complete one row at a time and cross-check that each row’s name matches the associated age/month/birthplace before moving on. Instafill.ai can reduce row-shift errors by extracting structured rows from the source and auto-mapping each value to the correct numbered row fields.

Saved over 80 hours a year

“I was never sure if my IRS forms like W-9 were filled correctly. Now, I can complete the forms accurately without any external help.”

Kevin Martin Green

Your data stays secure with advanced protection from Instafill and our subprocessors

Robust compliance program

Transparent business model

You’re not the product. You always know where your data is and what it is processed for.

ISO 27001, HIPAA, and GDPR

Our subprocesses adhere to multiple compliance standards, including but not limited to ISO 27001, HIPAA, and GDPR.

Security & privacy by design

We consider security and privacy from the initial design phase of any new service or functionality. It’s not an afterthought, it’s built-in, including support for two-factor authentication (2FA) to further protect your account.

Fill out Canada Census 1911 (Table A1) with Instafill.ai

Worried about filling PDFs wrong? Instafill securely fills fifth-census-of-canada-1911-canadian-census-form-table-a1-population-personal-description forms, ensuring each field is accurate.